Ostertagia In Cattle

The main roundworm of cattle isOstertagia ostertagi, known commonly as the brown stomach worm. Control of ostertagia will incidentally control other roundworms of lesser importance, such as the small intestinal worm (Cooperia sp). Occasionally, the stomach hairworm (Trichostrongylus axei) can be the predominant parasite but, more importantly, it is the only roundworm species that infects both sheep and cattle.

Life cycle

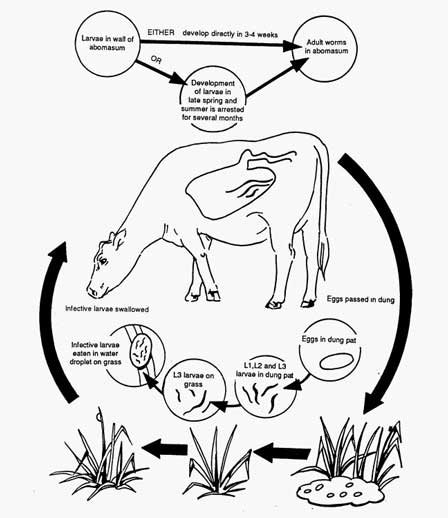

Ostertagia and other roundworms of cattle have a simple direct life cycle, as shown in Figure 1. An important feature of this life cycle is that it consists of two stages; the free-living stage on pasture and parasitic stage in cattle.

Figure 1

Eggs from mature females in the abomasum (fourth stomach) are passed in the dung. These hatch in the dung pat to first-stage larvae (L1). These larvae grow and moult to second-stage larvae (L2). The second-stage larvae continue to feed on bacteria in the dung pat and moult to become third-stage or infective larvae (L3).

The third-stage larvae (L3) cannot feed, because they retain the cuticle ("skin") from the second stage (L2) as a protective sheath, but can survive for long periods within the dung pat. They can also move some distance away from the dung pat. The parasitic stage of the ostertagia's life cycle begins when a beast ingests L3 larvae.

In the forestomachs the L3 larvae lose their protective sheaths. They then burrow into the glands of the wall of the abomasum. After moulting to become early fourth stage-larvae (L4), development may continue without delay or be interrupted by a period of up to several months. The lining of the abomasum is significantly damaged when the larvae emerge as immature adult worms.

Large numbers of L4 larvae tend to become inhibited in their development if they are ingested during spring and early summer. These can cause a serious type-2 disease when they resume growth and emerge into the abomasum during late summer and early autumn.

If the L4 larvae develop directly, that is if they don't become inhibited, then adult worms appear 3-4 weeks after infection with L3 larvae.

The disease

There are two types of disease caused by ostertagia. The signs of each type result from the same damage to the abomasum:

Type-1 disease usually occurs in calves and young cattle that have high burdens of adult worms in winter and spring. This disease follows rapid infection with large numbers of L3 larvae from heavily contaminated pastures in the autumn and winter after weaning. Dairy calves typically suffer type-1 disease at 5-6 months. Beef cattle are affected at 15-20 months.

Type-2 disease occurs especially in beef cows calving for the first and second time in the autumn and winter. This coincides with the stress of calving and the emergence of thousands of inhibited L4 larvae from the lining of the stomach. Severe scouring, loss of weight and even death may result. Frequent drenching may be needed just to keep these cattle alive.

Outbreaks of type-2 disease caused by ostertagia have become less common in beef cattle in recent years compared to the frequent and severe autumn outbreaks seen in the 1970s. The reason for this decline has been the introduction of the second generation benzimidazole (white) and macrocyclic lactone (mectin) drenches, and lower stocking rates of cattle on most properties.

Drenches

Four groups of drenches are available for use in cattle. All are effective against adult worms in the abomasum. They differ in their activity against the developing and inhibited L4 stages of larvae.

Group 1 - the benzimidazole or white drenches

Group 2 - levamisole or clear drenches

Group 3 - macrocyclic lactone (ML) or mectin drenches

Group 4 - combination drenches

The mectins (Group 3) are the most effective against L4 larvae, the benzimidazole or white drenches (Group 1) follow the mectins and the levamisole (clear drench) group (Group 2) is the least effective.

Some of the drenches in Group 1 (benzimidazoles) have lesser and a more variable effect on the immature and inhibited stages of Ostertagia than previously thought.

Where stocking rates for cattle are high or ostertagiasis is a problem, the use of Group 3 rather than drenches from Group 1 is recommended. Beef calves less than 12 weeks old need not be drenched as they won't be significantly infected with worms. Dairy calves only rarely need drenching before 12 weeks of age. Seek veterinary advice.

The route of administration of drenches (oral, injection, or pour-on) may influence the efficacy of the drench. Oral drenches may be rendered less effective if they bypass the rumen and go directly into the abomasum of some animals.

The pour-on formulations of levamisole have also given variable results in adult cattle in winter. The concentration of the drug in these formulations has been increased in response to these findings, but the lack of effect of levamisole on the inhibited larvae of Ostertagia means that levamisole-based drenches are not ideally suited for use in beef cattle over 12 months old.

Drench resistance is looming as a real threat for cattle farmers, with ML resistance in cattle parasites present in western Victoria and especially in New Zealand. The combination drench Eclipse® Pour-On (abamectin + levamisole) can slow down the development of resistance and is also effective against parasites that have developed resistance to one or the other of the ingredients.

Control programs - Beef Cattle

Integrated control strategies which combine drenching with movement of cattle to lower risk pasture, will maximise the benefits of drenching by reducing reinfection with L3 larvae. It has been demonstrated that alternative grazing with sheep and cattle has beneficial effects for worm control in both species, as they share only one species of worm and this is of intermediate importance.

Lower risk pastures are those that have low numbers of L3 larvae. These are newly sown pastures, hay aftermath, crop stubbles, fodder crops and pastures that were grazed - since the previous autumn break - solely by sheep or adult cattle over four years of age.

The recommended drenching program for autumn calving beef cattle in southern Victoria is:

January - weaners, first-calf heifers, second calvers and bulls

March/April - weaners, bulls and first-calf heifers

July - weaners only (and shift to low-risk paddock).

Note that routine treatment of adult cows after their second calving is not needed. Individual cows in this group may be treated if they are scouring or losing condition because of infection with ostertagia.

Control programs - Dairy Cattle

In dairy herds, infections caused by roundworm can be a major disease of weaned calves in their first winter. This is mainly where calves are reared year after year on the same paddock. As a result, L3 larvae can build up to great numbers. In contrast, adult dairy cows are relatively resistant to worms because of their age and previous infection. Ostertagiasis is even less common in adult dairy cattle than in beef cattle, although occasional cases, especially around the time of calving, do occur.

It is debatable whether low levels of infection with worms affect production of milk. Many conflicting studies have been published and it has been generally accepted that the cost of treating dairy cows to control low burdens of worms exceeds the gains of any additional milk production. Some trials conducted over the last 10 years have recorded responses after treatment with mectins of up to 0.5 L of milk per cow per day. In addition, some drenches cannot be used on lactating dairy cattle.

Routine treatment of adult dairy cows is not generally recommended and only the few individual animals that show signs of disease generally need to be drenched. Treatment of dairy cattle at calving or immediately after it may give a small increase in production of milk in herds that are heavily stocked because it is much easier for cattle to pick up L3 larvae from short spring pastures. However, better nutrition of the herd will produce far greater benefits than drenching.

Farmers should concentrate on reducing infection in weaned calves. The same principles concerning lower-risk paddocks apply to dairy cattle and to beef cattle. It is worthwhile rotating paddocks used for calf rearing from year to year, and practicing rotational grazing to provide lower-risk paddocks and improved nutrition. Heifers may need drenching at intervals of two to three months from the time of weaning until eight months of age. The exact frequency will depend on the degree of contamination of the pasture. Irrigation assists the movement of infective larvae from the dung pat to the herbage in much the same way as abundant summer rain does. For this reason there can be significant infections in cattle on irrigated pasture in summer as well as in autumn and winter.

Dairy bulls should be drenched in January and April.

Monitor Worms and Drench Efficacy

Worm egg counts conducted on dung samples (e.g. Wormtest) are used to indicate the worm burden in young cattle. WECs are less reliable in cattle older than 12 months.

Use WECs to monitor the level of worms and determine if drenching is needed or not.

Measure the effectiveness of drenching by conducting a second Wormtest two weeks after drenching.

John Larsen, formerly Ballarat and Noel Campbell, Attwood

© The State of Victoria, Department of Primary Industries. This material may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or consequences which may arise from your relying on any information contained in this material.

By Agriculture Victoria - Last updated 1 September 2015